Autori: M. Trümper, T. Lappi, A. Fino

Scarica l’articolo in formato .pdf: The Gymnasium of Agrigento: Report of the Second Excavation Campaign in 2023

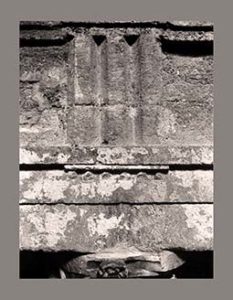

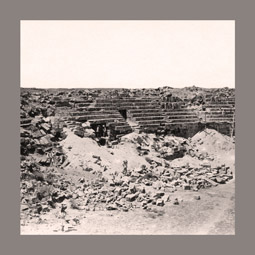

Il ginnasio di Agrigento è stato scavato tra gli anni Cinquanta del secolo scorso e il 2005 e, sebbene siano state messe in luce parti di una pista e una piscina tra due stenopoi, non è stato possibile determinare con sicurezza né l’estensione, né l’esistenza di una palaestra, né la data di costruzione. Un progetto avviato nel 2019 in collaborazione tra il Parco Archeologico e Paesaggistico Valle dei Templi di Agrigento, la Freie Universität di Berlino e il Politecnico di Bari sta indagando su questo aspetto. Sulla base dei risultati di prospezioni geofisiche effettuate nel 2020, sono state effettuate due campagne di scavo nel 2022 e nel 2023 in un campo a Nord della piscina, dove molto probabilmente era collocata la palaestra. In questo articolo è sono presentati i risultati della campagna del 2023, discussi in modo sintetico, concentrandosi sulla cronologia e sulla costruzione dello stenopos occidentale, sulla topografia, sulle dimensioni e sulla suddivisione del lotto della palaestra, sulla tecnica costruttiva delle strutture e sugli elementi architettonici più significativi. In particolare, è stato identificato con sicurezza un livello stradale nello stenopos che venne realizzato contestualmente alla palaestra, oltre ad una tubazione di drenaggio potrebbe appartenere alla fase originaria o a un rifacimento di poco successivo. Il lotto della palaestra doveva misurare massimo m 62,50 Nord-Sud e minimo m 35 Est-Ovest ed era suddiviso in almeno due diverse terrazze. Il rinvenimento di una tegola con bollo ΓΥΜ proveniente da uno strato di abbandono/distruzione dimostra che il lotto dove si ipotizza la palaestra apparteneva al ginnasio. Ciò è confermato da numerosi muri in blocchi di buona fattura, coerenti per orientamento, tecnica costruttiva e materiale con i muri del ginnasio precedentemente scavati. Si possono individuare almeno quattro ambienti sulla terrazza inferiore accanto alla piscina (tra cui forse un loutron e un’esedra con banchine) e un ampio vestibolo sulla terrazza superiore. Mentre due cornici con sima di un colonnato dorico sono state rinvenute nel 2022 e nel 2023 sulla terrazza inferiore, non è ancora possibile determinare la posizione e le dimensioni del cortile del peristilio. L’analisi degli elementi architettonici scavati nel lotto della palaestra propone una datazione per la costruzione al II secolo a.C. e le osservazioni condotte sulla piscina hanno permesso di ricostruirla come una grande vasca di m 15 Nord-Sud x m 7,65 Est-Ovest con accesso da una scala nell’angolo sud-ovest composta di 13 gradini a ridosso della parete occidentale.

Il ginnasio di Agrigento è stato scavato tra gli anni Cinquanta del secolo scorso e il 2005 e, sebbene siano state messe in luce parti di una pista e una piscina tra due stenopoi, non è stato possibile determinare con sicurezza né l’estensione, né l’esistenza di una palaestra, né la data di costruzione. Un progetto avviato nel 2019 in collaborazione tra il Parco Archeologico e Paesaggistico Valle dei Templi di Agrigento, la Freie Universität di Berlino e il Politecnico di Bari sta indagando su questo aspetto. Sulla base dei risultati di prospezioni geofisiche effettuate nel 2020, sono state effettuate due campagne di scavo nel 2022 e nel 2023 in un campo a Nord della piscina, dove molto probabilmente era collocata la palaestra. In questo articolo è sono presentati i risultati della campagna del 2023, discussi in modo sintetico, concentrandosi sulla cronologia e sulla costruzione dello stenopos occidentale, sulla topografia, sulle dimensioni e sulla suddivisione del lotto della palaestra, sulla tecnica costruttiva delle strutture e sugli elementi architettonici più significativi. In particolare, è stato identificato con sicurezza un livello stradale nello stenopos che venne realizzato contestualmente alla palaestra, oltre ad una tubazione di drenaggio potrebbe appartenere alla fase originaria o a un rifacimento di poco successivo. Il lotto della palaestra doveva misurare massimo m 62,50 Nord-Sud e minimo m 35 Est-Ovest ed era suddiviso in almeno due diverse terrazze. Il rinvenimento di una tegola con bollo ΓΥΜ proveniente da uno strato di abbandono/distruzione dimostra che il lotto dove si ipotizza la palaestra apparteneva al ginnasio. Ciò è confermato da numerosi muri in blocchi di buona fattura, coerenti per orientamento, tecnica costruttiva e materiale con i muri del ginnasio precedentemente scavati. Si possono individuare almeno quattro ambienti sulla terrazza inferiore accanto alla piscina (tra cui forse un loutron e un’esedra con banchine) e un ampio vestibolo sulla terrazza superiore. Mentre due cornici con sima di un colonnato dorico sono state rinvenute nel 2022 e nel 2023 sulla terrazza inferiore, non è ancora possibile determinare la posizione e le dimensioni del cortile del peristilio. L’analisi degli elementi architettonici scavati nel lotto della palaestra propone una datazione per la costruzione al II secolo a.C. e le osservazioni condotte sulla piscina hanno permesso di ricostruirla come una grande vasca di m 15 Nord-Sud x m 7,65 Est-Ovest con accesso da una scala nell’angolo sud-ovest composta di 13 gradini a ridosso della parete occidentale.

The gymnasium of Agrigento has been excavated between the 1950s and 2005. While parts of a race-track section and a pool were revealed between two stenopoi, the extension of the gymnasium and particularly the existence of a palaestra as well as the construction date could not be securely determined. A project launched in 2019 in cooperation between the Parco Archeologico e Paesaggistico Valle dei Templi di Agrigento, the Freie Universität Berlin, and the Politecnico di Bari aims to solve these questions. Based on the results of a geophysical survey carried out in 2020, two excavation campaigns were carried out in 2022 and 2023 in a field to the North of the pool where the palaestra was most likely located. The aim of this paper is to discuss the major results of the 2023 campaign that included ten stratigraphic trenches and an architectural survey. Results are discussed in a synthetic manner, focusing on the chronology and construction of the western stenopos; the topography, size, and subdivision of the palaestra lot; the construction technique of the walls; and significant architectural elements. One street level can be securely identified in the stenopos that was made together with the palaestra; a drainage pipe may have belonged to the original phase or a slightly later remodeling. The palaestra lot had an extension of maximally 62.50m North-South x minimally 35m East-West and was subdivided into at least two different terraces. A stamped tile with ΓΥΜ from an abandonment/destruction layer proves that the palaestra lot belonged to the gymnasium. This is confirmed by numerous well-made ashlar walls that are consistent in orientation, building technique, and material with the previously exposed walls of the gymnasium. At least four rooms can be identified on the lower terrace next to the pool (among them possibly a loutron and an exedra with benches) and a large vestibule on the upper terrace. While two cornices with sima from a Doric colonnade were found in 2022 and 2023 on the lower terrace, the location and size of the peristyle courtyard cannot yet be determined. The analysis of the architecture focused on the pool and architectural elements excavated in the palaestra lot. It supports a construction date of the gymnasium in the 2nd century BC and allows reconstructing the pool with a size of 15m North-South x 7.65m East-West and a staircase in the southwest corner, with 13 steps along the west wall.